Michael P. Shead

Senior Paper

International Community Development

Oral Roberts University

Tulsa, Oklahoma

December 7, 1999

Part II: The Community Development Project

Leadership training among the Navajo men between ages 12 and 17 in the Shiprock Agency of the Navajo Nation Reservation.

A Note From the Researcher.

A comprehensive documentation of the needs and suggested solutions for any people group would probably fill volumes. This document is not, by any means, an attempt to address all the needs of the Navajo people but to identify specific leadership issues and present a possible solution in this area.

This project is an effort to contribute an organized leadership training program for young Navajo men. Its purpose is to train up young leaders who know Jesus Christ as Savior and friend and who will be able, honest, and wise leaders in every area of Navajo life. This project will take on several stages before completion: analysis, design, development, implementation, evaluation and empowerment.

Michael Shead

Tulsa, 1999

Chapter 3: Navajo Background

Researchers must analyze historical, geographical, and political information to understand the present day situations and the source of leadership needs among the Navajo. This document will specifically look at needs that will be addressed by the leadership development program.

The Navajo are a diverse people. Through the years some have carried on the traditions and are still very connected with their land in a spiritual as well as physical sense. Some have found a way to relate to modern American society in border towns and large cities, while retaining their relations with Navajo language and traditions on the reservation. Others are very traditional and carry on the language and many of the old way of Navajo life, avoiding modernization except for necessities. Opposite the traditional Navajo are those who have minimal or no contact with traditions and language of the Navajo. Often these have moved to large cities and away from the reservation.

The Past

According to “The Rag Tag” Navajo comes from a spanish term for “thief”– a title well-deserved in years past (July-Sept, 1999). However, the reprisals and punishment brought on these people for their actions and responses were extreme. Punishment included immense persecution and trials–whether just or not–under the direction of U.S. Army Brigadier General James H. Carleton (Bailey, 1964). After decimating the crops, orchards, and homes and destroying many of the Navajo families through death and Ute slave traders, Carleton’s forced removal of the Navajo was begun.

In early March, 1864, 1,443 were the first of many Navajo to began what is forever remembered by these people as “The Long Walk” (Locke, 1992 pg. 361). This was a forced walk, some 400 miles long in cold weather which took the Navajo from their homeland which included much of the present-day Navajo Reservation to Bosque Redondo–a wretched alkali-ladden plot of land–in southern New Mexico. Bosque Redondo was described as a “flat, wind-swept reservation situated on the open plains east of the Rio Grande” (Bailey, 1964, pg. 166). The unfamiliar land and food, crop failures, and sickness made the exiled Navajo long all the more for their homeland.

During discussions with Army officials in May of 1868, Navajo headman, Barboncito proved himself most eloquent. The official offered to send them to Cherokee Territory (present day Oklahoma), yet Barboncito pled to be returned to their homeland. He described the boundaries of their land as established by their traditions and forefathers. Barboncito attributed the cause of so many deaths among the Navajo to the foreign land where they were being held. “…I think that our coming here has been the cause of so much death among us and our animals.” (Locke, 1992, pg. 383).

With the eloquent requests of Barboncito, the Navajo people were finally granted a favorable release. On June 18, 1868, the Dine’ were finally lining up with smiles on their faces as they walked toward their beloved Dinehtah–Navajoland. All in all, the preceding years of ravaging and the four years at Bosque Redondo left only 7,304 Navajos held on the Bosque Redondo reservation. Two thousand had died and about 1,000 had escaped, been captured or were unaccounted for. (Locke, 1992, pg. 382 & 386).

Despite such treatment by United States Government officials, this researcher noted very little bitterness against Billilagaana, as the Navajo call Anglos. They carry suspicion for overzealous outsiders but not outright hatred. The history of The Long Walk is important to know when attempting to relate and understand the Navajo people today.

The Land — Dine’tah (Navajoland)

One thing a person who takes any time to study or converse with a Navajo will realize is that, to consider the people, you must also consider their land; for their history, culture and very lives are closely tied to the land their ancestors walked. To know the people; know their land.

One thing a person who takes any time to study or converse with a Navajo will realize is that, to consider the people, you must also consider their land; for their history, culture and very lives are closely tied to the land their ancestors walked. To know the people; know their land.

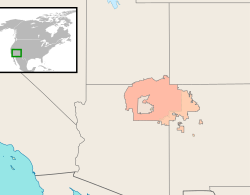

The Navajo Nation is situated on 25,351.4 square miles on the Colorado Plateau spanning northwest New Mexico, southeast Utah, and the majority of northeastern Arizona. Located at the joining of these three states and Colorado, the Navajo Nation spreads out to the east, west, and south. The land varies from prairies, hills, mesas and canyons, to pine and pinion covered mountains. In a recent visit to this region, the researcher found the land to hold a rugged beauty in the stone carved by wind, rain, and ancient volcanoes. This land is a rugged rocky land where canyons are common and fertile fields of grass or crops are irrigated with water from nearby rivers. The climate is typically arid and semiarid (Rodgers, 1995, Spring, pg. 1).

The reservation is a vast area. Most homes are in small family clusters all across the reservation. Although a few paved roads provide access to the villages and trading posts, most of the residences can only be found along gravel and dirt roads. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is almost a necessity for some roads and trails. It would be difficult to traverse many of the back roads and steep grades without one.

The Politics

The Navajo Nation is, in some ways considered to be, a nation of its own within the United States, yet, in others, it is very subject to the federal government of the U.S. The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is governed by the U.S. Department of Interior, which lists the BIA alongside national projects in mineral resources, wildlife, and national parks (Department of Interior, 1999). Placement of the American Indians alongside national resources has not gone unnoticed by the Navajos. Some of them feel this listing puts the American Indians on the level of just another resource to be put to use by the government (personal correspondence, June, 1999).

Below the federal government is the tribal government which overseas the entire reservation. The tribal government is a democratic three-branched government with judicial, legislative and executive branches elected by the people. Local government officials make up what are called chapters or local community leadership. There are 110 Navajo chapters ( Navajo Nation, 1999). Every Navajo belongs to a chapter according to their family’s land location on the Reservation. T.H. Lee said that even if a Navajo moves off the Reservation that person is still eligible to return and vote at their Chapter house (personal correspondence, June, 1999). These Chapters are the equivalent of county seats for the 110 regions of the reservation.

In each Chapter there is a chapter house which serves as the center of community activities. Events such as civil meetings, elections, library services, daycare, meals for the elderly, and other community services are based out of the chapter houses.

The Religions

In the Navajo language there is no word for religion because beliefs are a way of life not something merely practiced occasionally. The various religious practices of the Navajo can be separated into three divisions: traditional, cultic, and Christian/Catholic.

According to Locke, the traditional Navajo ceremonies, songs legends, and rites are described as the “Navajo Way” (1992, pg. xv). The Navajo Way has prescribed directions for cleansing rituals, the way a hogan–the Navajo round house–is laid out, and even how weaving patterns are designed. The traditional Navajo is very close to nature and sees nature as his master. The traditionalist thinks that although nature may be controlled to a certain extent it should not and cannot be mastered by man (Locke, 1992, pg. 31).

Witchcraft–the “dark side” of Navajo traditional beliefs–is based on the idea that people, who make a pact with the evil spirits in order to become rich, receive special powers of destruction. These witches or chindi are known to go about the night in wolf or coyote skins. They supposedly can turn themselves into wolves as they go about doing harm to the individuals they dislike. Chindi are feared and hated even in present day. According to Locke, for one to become a chindi, they must go through an elaborate secret ceremony and designate one of their relatives as a sacrifice to be killed for them to receive the evil powers. Though they are feared, they are hated even more. In the past the chindi were even subject to witch hunts by Navajo leaders who tried and killed those convicted of such practices (Locke, 1992, pg. 30). The concept of Navajo witchcraft still has active followers today. Al Atson, a Navajo pastor and construction worker, related several encounters with evil spirits and with chindi both in attacks against his person and in late night encounters (personal correspondence, June, 1999).

The Navajo list of deities does not have one supreme deity, rather many important deities and some lesser divine beings. The list includes such names as Changing Woman–a benevolent creator, Sun, First Man, First Woman, the Hero Twins, and many others collectively called the Holy People. Except for Changing Woman the deities have both good and dangerous tendencies concerning helping or harming humanity (Locke, 1992, pg. 46).

The Yeis are grandfather deities who are impersonated by actors in elaborate costumes during Night Chants called Yeibichai. These nine-day ceremonies initiate children between the ages of seven and thirteen into the ceremonial world of the adult Navajo. The extensive ceremony is carried out in a precise manner under fear of a mistake by either the singer or the participant. Mistakes are said to result in crippling or loss of sight or hearing (Locke, 1992, pg. 49). There are still many celebrations and traditional dances, art work, and festivals which have very strong religious and spiritual backgrounds.

Each year there is a commercialized festival held in Shiprock, N.M., which includes appearances by Yei impersonators who expect gifts from those they bless and others as well. R.G. “Squeek” Hunt, Jr., owner of a butcher shop near Shiprock, said that it is common that during that time of year impersonators will await customers coming out of the store and expect gifts from customers and the meat lockers. If they do not get the pieces they want from the customers, Hunt said they just take them anyway. He seemed quite comfortable with this cultural ceremony even at his doorstep (personal correspondence, June, 1999).

Peyote, a hallucinogenic drug made from a certain cactus plant (Insel & Roth, 1998, pg. 232), is illegal to use except in ceremonies at what has become known as the Native American Church. Sites where these hallucination ceremonies take place can be noted as one drives across the Reservation by the distinct teepees which usually denote the location of one of these peyote ceremonies. The teepee also denotes the fact that peyote religions did not originate among the Navajo but came from the plains Indians (T.H. Lee, personal correspondence, June, 1999). Despite its origination, the Peyote cult has drawn many Navajo followers. According to the Navajo Nation publication, Chapter Images, in 1992 the Native American Church often has double or more the members than other churches, and is very active in nearly every chapter. In 1992 the Hogback Chapter had no churches. The Images book noted membership in the Native American Church as “majority of population” in that chapter. In most chapters the members of the Native American Church well outnumbered the members of the traditional churches (Rodgers, 1993, Fall).

Other cultic groups also have extensive influences on the Navajo Reservation. These include the Mormons and Jehovah Witnesses who have many missions, churches and followers on the Reservation (Rodgers, 1993, Fall).

The third religious division–Christian/Catholic–has 338 churches in 108 of the 110 chapters (Rodgers, 1993, Fall). Despite this representation on the reservation there are many internal divisions among the churches themselves which thwart the cause of Christ–divisions such as, mistrust, poor leadership, self-honor, pride, and shallow reasoning.

T.H. Lee said that Anglos have been evangelizing the Navajo for centuries but they often have looked at the people as children who are unable to become leaders themselves. Thus when Navajo pastors eventually do take on leadership skills they tend to be self-reliant leaders who do not raise up others to take part in developing the church and people. There is still much distrust between Navajo and Anglo church leadership as well as Navajo to Navajo leadership. Lee said many Christian Navajos expect him to take on all the leadership and responsibilities of the churches he is involved with, yet he is trying to train up people who can lead themselves in churches that will work together to lead others to Christ not to use the church as an egotistical opportunity to control people. Often those who have leadership skills are offended or pushed out of the church because the present pastor sees them as a threat to his authority. Then when the rejected leaders start their own churches, the backbiting continues. Leadership is not developed and consequently few feel they have a part, and numerical and spiritual growth is stunted (T.H. Lee, personal correspondence, June, 1999).

Often the regular church services have few in attendance and those who do come are mostly women unless a special event–revival, vacation Bible school, or some sort of celebration–is held. Few want to commit to a cause but choose to take part in the short-term excitement of such events as listed in the sentence above. According to Lee, establishing and determining goals is difficult for the Navajo church leaders. “It is really hard for Navajo people to learn the value of goal setting,” Lee said. “I don’t think they have ever set down and set goals (for the church).” (personal correspondence, June, 1999). This goal-setting issue will be addressed in the Project segment of this document.

Chapter 4: Community Needs

The Community

When considering a group of people for development it is necessary to define who the people are, where they live and provide a general description of these people. This people and location described in the definition and description will be called “the community”.

As noted by the historical background in the preceding chapter this project is for the Navajo people. More specifically, Navajo males between the ages of 12 and 17 who live within the Shiprock Agency and nearby cities. According to the Chapter Images: 1992, the Shiprock Agency has twenty chapters spanning Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico. Population for 1993 was estimated to be 27,846 (Rodgers, 1993, Fall). Twenty-two percent of the Navajo Nation population are between 10 and 19 years of age. That is over 33,000 young people between these ages on the reservation of 151,105. According to these figures the number of 10- to 19-year-old children in the Shiprock Agency is just over 6,000 (Division of Community Development, 1993, pg. 37).

The Current Needs

With an understanding of the Navajo’s history and the things which have molded their attitude, one is then able to move on toward the present situation and analyze the current needs of the people in this community..

Although knowledge of the past helps to understand the background of any people, no developer should ever rely solely on the past to gain understanding of a people group today. The present situation shows the development of new social problems, attitudes, and needs not found historically.

In this description of needs the researcher will consider the needs as described and observed while he visited the Shiprock Agency and Farmington, N.M., for three weeks in June of 1999.

The leadership needs of the Navajo people can be divided into four areas: Personal, Family, Faith, and Work. Leadership is needed in all these areas.

First, consider the area of personal responsibility. Doug Taylor, the Anglo grounds keeper for the American Indian Bible Ministries in Farmington, told of an incident of what seemed to be neglect and irresponsiblity among some of the young Navajo men for whom he holds weekly events (personal correspondence, June, 1999).

Several items were loaned to a certain boy who was made aware that Taylor expected these fishing items to be returned to him. With apparent neglect and lack of concern the items were never returned and when Taylor inquired of them they had been “loaned” to another person by the boy, Taylor said. Through leadership training, personal responsiblity and respect for others could be built up. Although this boy seemed not to care about the possessions of another, this may be due, in part, to a community “everyone owns everything” attitude. For a people like this it would be important to promote the positiveness of helping others and sharing of goods but also the responsibility to care for and return those items.

Personal responsiblity also must be addressed in the area of consumption of alcohol and drugs. Alcoholism is a common problem which the Navajo Nation is working to combat, though the “drunk Indian” term is an unfair stereotype. One contribution to the alcoholism and lack of work ethic among some of the Navajo is similar to many Americans. The government programs which provide finances often instill a sedentary lifestyle in both Anglo and Navajo recipients. The researcher was told about some Navajo who spend much of their time on the reservation drinking rather than in profitable leasure and work that would improve themselves. Although this is illegal, bootlegging has become a very profitable undertaking on the reservation where no alcohol is allowed but drinking is common knowledge (T.H. Lee, personal correspondence, June, 1999).

Daniel Yazzie noted that gambling is also a problem. He said that both alcohol and gambling are a result of a problem which spans the generations–having nothing to do. Yazzie said that even the older members of society have these problems (personal correspondence, June 1999).

To promote personal leadership and resistance to these social vices this project will entail various work activities and character building exercises which should provide a sense of dignity and self respect while promoting abstinence from these products.

Family

The next leadership needs area would, in a large way, be taken care of if the people learned the personal disciplines included in the above discussion. This area is the family.

Navajo family lines were mostly maternal. When a couple married, the husband would leave his family and live with his wife on her family’s land. Although descent used to be traced through the mother, the matriarchal system is not as strictly practiced as in the past (Locke, 1992, pg. 16 – 17). Despite the matriarchal system and the home leadership of the mothers, it is important to train up young men to be faithful in marriage and as the paternal providers who bring in the finances for the operation of the family. In the past the fathers were the ones who protected the community, cared for the horses, and brought meat. Today leadership for men may carry on this role of protection through moral training, care for transportation through automobile repair, and provision of food though an occupation or craft.

In the church and a revival service the researcher visited, he noted a majority of women who are active and faithfully involved in carrying out the Christian faith. This leadership program would train up young men in the teachings of Jesus Christ Himself. With lessons derived from Jesus’ messages to the disciples, the boys would be exposed to Christ in a way that would–hopefully–build a love for Christ and desire to serve Him that would last into eternity. This leadership in faith would transcend the personality battles which have arisen among pastors who fail to raise up new leaders but take on all the responsibilities themselves. The idea behind teaching the leadership of Jesus Christ is to instill in the participants of the project the understanding that following the example of Jesus Christ is something to be done at all times and not only in the religious cermonies called church.

Leadership in the area of work is the final area to be addressed in this project. This follows the lead of the first two areas: Personal and Family. As someone becomes responsible and faithful in the area of leadership and following the teachings of Jesus Christ, they will not become so bored and distracted by vices that they fall into the life-problems and difficulties brought on by these or the very real spiritual fears involved in the ancient beliefs. They will remain active in positive occupations using faith, talents, and training they have enjoyed obtaining.

Chapter 5: Project Layout

The Steps

In the process of learning about the people and their needs, the first step of the development is being walked out. That first step is to establish credibility with the people and develop a level of trust with them that will allow the developer, not only to begin this project, but to get current community leaders involved and eventually turn the program over to new leaders.

The second step is to define the purpose and goals of this program. Without defined goals and a direction to follow, a project would wander and never achieve lasting results. Well thought out goals and a founding purpose will draw community leadership in support.

With the goals established the third step may begin–scheduling. Then comes the fourth step of gathering resources before the next step of actually developing the process for teaching and training the participants. Upon completion of this step, the plan may be implemented.

Each development project ends with the final step–gradual empowerment. In this stage the local leadership is given complete control of the project and the outside developer is removed from the project.

The Layout

Contacts

The Shiprock agency is evaluated through personal visits of the developer, interviews with local leaders, some of the general population, and demographic research. Personal visits and interviews would first be made with officials at The Dine’ College in Shiprock, N.M., pastors in the Farmington area, and the executive director of the Farmington Inter-tribal Indian Organization. Also excellent contacts can be made through the local industries like Navajo Agricultural Products Industry (NAPI) and the Four Corners Coal-Powered Generating Station. (These would be possible corporate supporters and even internship sites in the future.)

The more Navajo contacts made the more opportunities to receive firsthand information about the people there will be. Key in establishing contacts is a genuine interest in how each person is helping or wants to help their people. As one person introduces the developer to another, more and more connections and information will be gained. Developers should find out needs but not focus on them so much that the community feels he is negative. Focus should be placed on the basic idea of the development program–building up more strong leaders who have a personal relationship with Christ.

Goals

As the needs are defined (which has been done in the previous chapter) goals can be established with the advice of the local contacts which have shown interest in this development work.

This discipleship/leadership program will give young Navajo men the opportunity to train their leadership skills, glean from other leaders both Navajo and Anglo, and evaluate themselves as leaders. Throughout the program the teachings and leadership example of Jesus Christ is an intimate part. Participants will have opportunities to take on leadership positions as they develop in each area.

For this leadership project the goals and proposed quality outcomes are:

1) Participants will be able to define servant leadership qualities as exemplified by Christ, develop ways to carry these out in their own community, and exemplify obedience to authority. Qualities displayed: Discipleship and obedience

2) Participants will display the ability to establish positive relationships with peers, adults, and children. Quality displayed: Relational skills

3) Participants will be able to plan a project, organize resources, and implement the proposed project. Quality displayed: Leadership

4) Participants will have an understanding of the satisfaction found in knowing Jesus Christ and helping others. Qualities displayed: Contentment and satisfaction in life.

5) Participants will be able to show understanding and proficient skill in a handcraft, art, or useful talent. Quality displayed: Workmanship

Project Design

With the above goals in mind, the project must now be designed to accomplish these goals. The following is the suggested design for this program. It should be considered, but evaluated for its effectiveness and appropriatness when actually put into action. Although the goals of the program include five areas, these will not be addressed separately, but as intimate qualities of a well-rounded leader.

The first two months would focus on activities which build relations between the participants and their mentors. Prayer to the God of Heaven whose Son is Jesus Christ should be a part of every meeting of this program. Suggested activities include: Introductory games (see Appendix B for suggestions), movie and ice cream, float trip on the San Juan River, and other activities as suggested by the advisory board. Small work projects can also be undertaken–work projects like: picking up trash in one of the participant’s neighborhoods or cleaning a grandparent’s yard.

Mentors should look at each activity as an opportunity to find out about the participant as well as share some of themselves with that individual. The mentor should always be willing to answer any question the honestly seeking participant may ask As the mentor shares personal experiences with the participant, the two should begin to share conversations about their life goals, what the mentor remembers about being the participants age, etc.

The group should also begin to learn to laugh together. If meetings are silent and solemn then the interaction desired is not being accomplished. At the beginning of each meeting there should be a short time of devotions or if the activity is conducive to this, life application and Christ-like examples may be explained during the activity.

This should also be a time for the mentors to be discovering what type of workmanship projects the participants are interested in. Observe what art, music, handcraft, writing, or occupational talents would they like to take part in. This information will be used in the third segement.

Note: Charts 1-6 summarize the methods being used to teach concepts during each bi-monthly segment. (Charts are not included in the online version of this document.)

Months 1-2

Chart 1

As the relationship building process continues, the next step begins. The participants will begin taking part in activities and training aimed more at discipleship and how to follow and grow under leadership. This is the second and third month segment.

These activities should include planned actions which require the participants to follow the instructions of a leader and result in a specific objective. With each activity a Scripture should be memorized by mentors and participants alike. These activities should include: a two-day hiking trip with a specific objective, location, or peak as the goal, a fishing trip, a game of Capture the Flag, construction of a small building that requires a foundation, and map reading activities. The objectives of these activities would be more than the accomplishment of the tasks. These activities will give mentors the opportunity to show the participants practical application of Biblical truths.

For the hiking trip, the object lesson can include qualities of steadfastness, keeping your eyes on the goal, and overcoming extended difficulties. Good campfire devotionals would include Philippians 3:12-16 in which Paul discusses “pressing toward the mark” that is–God’s calling for them.

The fishing trip would give opportunities to teach patience, persistence, and quiet reflection on God and His nature. Also lessons can be drawn from the examples Christ gave to His disciples concerning following His call and becoming fishers of men.

The Capture the Flag game teaches planning, group organization, and teamwork. Participants should be explained that as in the game of Capture the Flag there is a specific object to attain, so in the life there is a goal but they must choose if they are going to follow the goal of Christ or the things of this world. They must count the cost both material and eternal and decide if they want to dedicate their life to Christ or themselves, then live this through the grace Christ paid for on the cross.

Note: this would be a good opportunity to really point out that they must make a decision. Ask if they want to make that now. Here are some scriptures to assist in this: Romans 1:21; Knowledge of God is not enough. Romans 3:10, 3:23; Everyone is a sinner. Romans 6:23; Sin equals death. Romans 5:8-9, John 3:16; God loves us even beyond our sin. Romans 8:2-3, 10:9,13; We can have life if we confess and believe.

Construction of a chicken house or storage building with a foundation gives the opportunity to teach the participants about the necessity of a firm foundation in life as well as for planning a building. Stress the necessity of building with quality materials and the Biblical life application of this concept. Useful Scriptures are: First Corinthians 3:11-16 and Matthew 7:13-27. This also gives the opportunity for the mentors to address drugs and alcohol as poor quality materials to be putting into the building of your body. If you use materials that are destructive in building your house then your house will fall down. If you use drugs and alcohol your body is being destroyed. This can ruin your life and seriously make limit the abilities you can give to God for His purposes.

The map reading exercise should include an adventure situation with a surprise waiting for them at the location found only by correctly reading the map. The mentors can draw their own maps or use existing maps to plan a course. The object lesson is that they must have the map, read it, and follow it in order to get where they want to go. So it is in life, the mentors should tell the participants, if you do not know what God wants you to do you can’t do it. The map God gives you is the Bible. Show them the parables of Christ and encourage them to read them. Then discuss a particular one the next week.

Months 2-3

Chart 2

The third segment begins in the fifth and sixth months of the program. Discipleship and encouragement of a personal relationship with Christ should be emphasized. This can be done through mentors sharing with their participants how they came to Christ and how He has been faithful to them. A Bible and quality Christian books should be given to the participants who show interest in reading more on their own. The importance of solid fellowship in a Bible-believing church should also be stressed and encouraged. This segment would be a good time to bring in someone who has been delivered from drugs and/or alcohol to discuss the danger of these. This discussion should be very frank and open. Let them ask any questions. Perhaps a visit to a local rehabilitation office would be appropriate. Also the servanthood of Christ’s leadership should also be given as an example of good leadership.

This segment will also introduce more emphasis on workmanship and quality work. Since participants have already been doing some construction projects in earlier segments, this will be a way to hone those skills and giving them the opportunity to experience a variety of work. Talents should be pulled from the mentors and advisors who are already a part of the program, but outside individuals may also be called upon if they are agreeable. The participants would be introduced to an art like photography, painting, pottery, sculpture, jewelry making, or sketching or a occupational talent like roofing, mechanics, construction, or painting. Music is another area which could be tapped. Guitar, flutes, traditional instruments, piano and whatever other musicians are available could be part of a concert where the participants could be introduced to the joy of music. If this is held at the end of the segment participants could also display their art or construction work. This would also be an ideal opportunity to teach the particpants how to organize a publicized event at the same time as giving some publicity to the Leadership Training Program.

Two months is not long enough to teach any of the above talents to a sufficiently proficient level but the hope is that the participants will catch a joy for one or two of these that can be encouraged and nurtured as the program continues. This is also another opportunity to stress the necessity of faithfulness and consistency in practice to get the quality of end results they desire. So it is in life, without consistent faithfulness in seeking after Christ other things will crowd out your relationship with Christ.

Months 5-6

Chart 3

In segment four (months seven and eight) the mentors and advisory board should reevaluate the program up to this point and decide what, if anything, has not been covered sufficiently or left out. If so these can be re-introduced or taught in this segment. Beyond these methods and concepts which are being re-introduced, the participants should be given a list of workmanship methods from those begun in the last segment. From that list the participants should select a pre-determined number of training areas from the categories of art, occupational talents, and music to be taught more extensively. These should be carried on in small groups of those who have chosen each training area.

Mentors should be careful not to advance too quickly but to really evaluate the relationships which have been built and be cautious to carry on building open relationships with these individuals. During this segment a special event of some sort (i.e. an all night party at a community building where games and ball can be played or some of the plans which were not completed in segment two can be used here). This should be used to bring all the participants together, to have a fun time, and at some point encourage them to think about what they have been doing for the past six months, what they have learned, and what they want to learn in the next six. Hold this group converation in a large circle and encourage them to speak up about their thoughts. Emphasize the need for evaluation of how they want to grow and recognition of qualities in each other. If these encouraging comments are written down they can be used to encourage the participants individually later.

Ask if they are satisfied with life. Satisfaction in life comes from seeking a worthy goal–Christ–and growing slowly but surely toward the person you know God wants you to be. Also address the truly amazing grace God has for us when we fail to live up to His or our own expectations. The mentors should be exemplifying this grace in their own lives.

For the rest of this segment, emphasize the contentment that can be found in knowing God and helping others know him also.

Months 7-8

Chart 4

In segment five the participants will start adjustment toward leadership themselves. After group prayer for wisdom, mentors should have the participants separate into groups of five and brainstorm about people they could help in some way. The mentors may need to prime the pump with ideas like: visiting a nursing home, showing the art and playing music at a nursing home, helping clean up a certain neighborhood, cleaning someone’s house, a sports day for local youth, gathering canned foods for someone in need, a mother’s day out babysitting-for-a-day program, and helping serve hot meals to the elderly at the chapter houses, etc.

Have the participants take notes of their ideas. Then, when everyone comes back together, have them present or write the ideas on an overhead or chalk board so everyone can read them. Break these down to four activites and have the participants plan them out. Mentors should be available for advice but the main planning should be done by the participants themselves. From each group a leader should be assigned by the group. Plans should be approved by mentors prior to any implementation. The rest of the segment should be used to pursue these plans and implementing them. Encourage the participants to share with others about their realtionship with Christ. Equate this ministry opportunity to how Jesus sent out His disciples in Matthew 10.

Months 9-10

Chart 5

In the final segment the activities from the last segment should be completed, evaluated by the participants and mentors together, and discussed in an all-group meeting. Mentors should ask questions like: What was the greatest obstacle you had to overcome to accomplish your goals? Did you accomplish your goals? Do you feel your group was able to work well together? Do you think you would do this differently next time? Would there be a next time? Why?

After discussing the concepts they have learned the participants should be required to take a test or write an essay on the topic of leadership including how Christ is an example of a leader, qualities of a leader, and the way they plan to use the skills and concepts learned in this program.

As a grand finale of the program the participants should make lists of the activities they did and note what concepts they feel they learned. A special certification ceremony should be held to recognize the growth and development of each who complete the program. The participants should be placed in charge of the planning which will follow guidelines provided by the mentors and advisory board. A short speech should be included noting the program’s goals and emphasis on a personal relationship with the God of the Bible and His Son Jesus. Mentors should also receive the opportunity to speak briefly about their participants and present each with the official certificate.

Parents, local leaders, and those who were a part of the activities should be invited to the event. A press release with pictures of the the participants working on some of the projects should be sent to local media sources to announce the special event. An invitation should be sent to a reporter or editor.

A call for new participants should be given to introduce the next year’s program. The certified participants should be invited to join for another year if they so choose. They would be a part of leading other participants and having more specific leadership training and mentoring in leadership and friendship with Jesus Christ. After completing the second year, a participant who shows interest will be assisted by the program leadership in finding an internship through one of the local businesses, industries or artisans.

Months 11-12

Chart 6

Considerations & Resources

With the layout and planning complete, issues of entrance regulations, financing, discipline, attendance, project length, financing, and selection of the mentor/teachers must be addressed.

A board of advisors–a majority of Navajos–should oversee the entire program and be available for advice, discipline, and decision making concerning the project. This involvement would help to establish the project as a community project for and by the Navajo and not merely some outside program.

Mentors for the program would be found through the contacts already made. Preferable to Anglos are the elder Navajos and local leaders who have displayed faithfulness in their churches, recognize Jesus Christ as their Savior, and are willing to be mentor/teachers. Other guest instructors would also be involved.

This project is specifically aimed at Navajo boys between the ages of 12 and 17 but advice of local leadership and the Navajo leaders who have provided advice in the research phase would be the basis for such stipulations.

Activities would be scheduled out so mentors and participants could plan for the entire segment (a two-month period) in advance. To accomodate participants and mentors, the activities would be on one day of each week except for certain extra curricular activities and possible personal mentor activities which could be set up individually. However, the meetings are planned they should be set to a consistent schedule. The leadership training would occur in two-month segments with six segments–a total of one year.

This length of time would allow relationships to be established and true discipleship and mentor training to occur. However, it is encouraged by this researcher that the program invite participants to continue taking part in the program for a period of three years to build solid relationships with mentors and Christ while also forming a solid foundation of leadership and perfecting talents. Participants who have already gone through the program can move on to advanced discipleship and activities and eventually apply their leadership training as they lead the younger groups through certain activities and take part in internships.

Before participants can enter the program they must meet a certain list of criteria: 1) Sign an honor code: of conduct, submission to instructors and mentors, and commitment for a two-month period (to be re-evaluated every two months). 2) Express openness to learning and applying the teachings of Jesus Christ as described in the Bible. 3) At least one parent or guardian must agree to the participant’s attendance.

Attendance should be mandatory with specific exceptions. A disciplinary action should be determined by the board for unexcused absences.

Financing for this program should be sought through area visionaries who see the value of such a program, local churches who have mentors from their congregations taking part, businesses who see the value of raising up young leaders with the qualities espoused in this program, and possible outside support.

Implementation

With the mentors selected, as soon as the facilities, possibly a mission or chapter house, can be located and transportation arranged; advertisment should begin among local youth, chapter houses, trading posts, churches, and businesses. As soon as approval of the participants has been completed the program may begin as layed out in the project design section of this document under the guidance of the advisory board.

Empowerment

Since most of the advisory board and many of the mentors are already Navajo, the empowerment process is already underway. Anglos who are taking part in this program should keep in mind that this should be a Navajo program with which they–the Anglos–are merely assisting, not leading. As more and more Navajo leaders get involved they should be given responsibilities. Although, as with any program, some of the new leaders may need encouragement to take on responsibility, as they take those positions of authority they should begin to take on an attitude of Navajo ownership for the program while continuing the basic beliefs of the program. Anglo leaders should be training up Navajo to take charge and carry the program on to grow and affect even more than the Anglos could have ever touched.

The Evaluation

Evaluation is occurring throughout this program. At the completion of each segment the advisory board and mentors should hold a meeting to discuss the accomplishments, problems, and possible changes for the program. This allows changes to occur throughout the program not only at the end of the entire program year. As a part of evaluation there should be a means set up for mentors to discuss individual concerns with the advisory board, but no action should be taken by the board until a proper representation of all parties involved have explained their actions when this is a conflict between mentors or the program leadership. Never should there be only one person completely in charge. The board of at least four non-related people should hold each other accountable and oversee all major decisions.

The evaluation process at the end of each segment should include mentor comments on how the participants have advanced during that two-month period, comments from outsiders who were helped or affected by the program, and comments from guests to the program. Evaluation should also be made of the scores or content of the essays by participants given in the final segment of the program. At the completion of each year, the evaluation will include a document listing how many students completed the program and requested permission to participate for another year, how many interns have been set up, how interns are accepted by their place of internment–to be evaluated by a questionnaire given to the director over that individual. Also a questionnaire should be given to participants to see how they evaluate the program.

———-

References

Bailey, L.R. (1964). The Long Walk. Los Angeles: Westernlore Press.

Beaver, R.P. (1970). The History of Mission Strategy. Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader (Revised ed.). (pp. B-58 – B-72). Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

Bunch, R. (1982). Two Ears of Corn: A guide to people-centered agriculture improvement. Oklahoma City :World Neighbors.

Dayton, E. R.(1979). Evangelism as Development. Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader (Revised ed.). (pp. D-210-D-212). Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

Division of Community Development. (1993). 1990 Census Population and Housing Characteristics of the Navajo Nation. Window Rock, AZ: The Navajo Nation

Fenton, H. (1973). Myths about Missions. Downer’s Grove, IL:Intervarsity Press.

Hipp, M.L. (1999, February 27). Address. Speech presented to the Heartland Missions Festival ‘99, Tulsa, OK.

Hoffman, B. (1995). ADDIE. Available: http://edweb.sdsu.edu/eet1/ADDIE/ADDIE.html

Hoffman B. (Retrieved Oct., 1999). Home page. Available: http://edweb.sdsu.edu/people/rhoffman/rhoffman.html

Hullinger, H. (1999, October 11). Address. International Community Development Seminar class, Oral Roberts University, Tulsa, OK.

Insel, P. M. and Roth, W. (8th ed.) (1998). Core Concepts in Health. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Katz, G. (1999, October 9). “Far from united: 10 years after the Wall came down, economics still keep Germans apart”. The Dallas Morning News. [Online version]. Available: http://www.dallasnews.com/world/1009int1wall.htm

Locke, R. F. (5th ed.). (1992). The Book of the Navajo.

Los Angeles: Mankind Publishing Company.

Navajo Nation Home Page (1999, Oct. 5). [Table of Contents]. Available: http://www.navajo.org/nntoc.html

Pickett, R.C. & Hawthorne, S.C. “Helping Others Help Themselves: Christian Community Development”. Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: